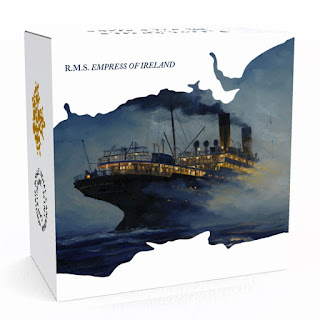

Canada 20 Dollars Silver Coin 2014 RMS Empress of Ireland

Lost Ships in Canadian Waters

Obverse: Susanna Blunt’s design of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Reverse: Designed by Canadian artist John Horton, your coin uses selective paint to recreate the imminent collision of RMS Empress of Ireland and the Norwegian collier Storstad during the early morning hours of May 29, 1914. Rolling in from the coast (engraved in the background), the thick fog comes between the two ships in the coloured centre portion of the image field. The shadowy image of the Storstad emerges from the right side of the image, its sharp bow in line to make contact with the Empress's starboard side. The passenger ship's stern and funnels are partially unobstructed by the fog in this image to provide a glimpse of the liner before tragedy would send it to its final resting place on the bottom of the St. Lawrence River.

Mintage: 7000.

Composition: fine silver (99.99% pure).

Finish: proof.

Weight: 31.39 g.

Diameter: 38 mm.

Edge: plain with edge lettering.

Face value: 20 Canadian Dollars.

Artist: John Horton (reverse), Susanna Blunt (obverse).

Special features:

• This coin commemorates the 100th anniversary of the loss of RMS Empress of Ireland and features edge-lettering that displays the ship's name, as well as a bell: one of the recovered artifacts from the wreck.

• This coin features a stunning colour portrait, framed within the coastline of the St. Lawrence seaway, and shows the RMS Empress of Ireland moments before her collision with the Storstad.

• This coin is the first in a 3-coin series that commemorates well-known vessels that have been lost in Canadian waters, and the stories that have emerged from the events surrounding their final fate.

• This coin is a prestigious addition to your Canadiana, history or commemorative display.

Packaging: This coin is encapsulated and presented in a Royal Canadian Mint-branded maroon clamshell with a custom beauty box.

Tragedy In A Gilded Age: The Story of the R.M.S. Empress Of Ireland

How do events become lost in time? Why are some tragedies memorialized profoundly while others fade into obscurity? In the case of the RMS Empress of Ireland, its drama was overshadowed by the devastation of the First World War, which began only months after the sinking. The Empress is also sandwiched in a triad of disastrous maritime events that took place between 1912 and 1915. The combined death toll from the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912, the RMS Empress of Ireland in 1914 and the RMS Lusitania in 1915 was almost 4,000. |

| formal portrait of Captain Henry Kendall (1864-1965), the last captain of RMS Empress of Ireland which sank in a collision with the SS Storstad in May 1914 |

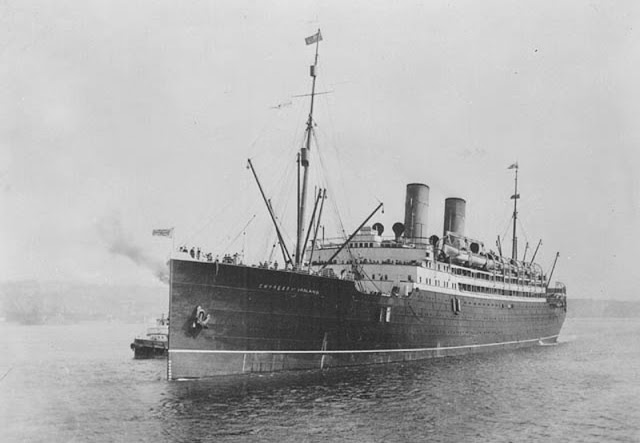

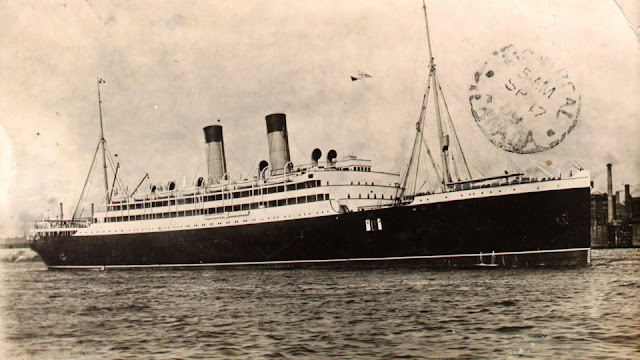

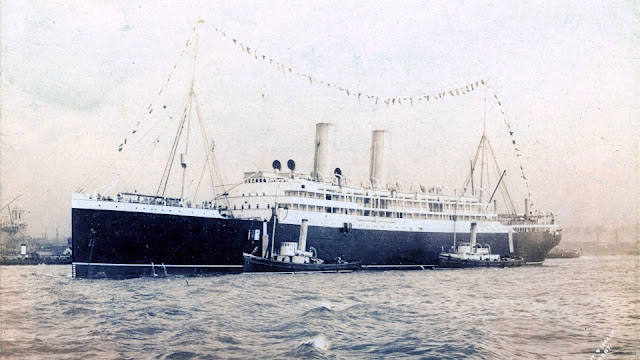

The RMS Empress of Ireland was commissioned by Canadian Pacific for the northern transatlantic route between Quebec and England. At this time, the route between New York and Southampton, England was the more popular voyage; to increase trade advantageously on the sea-lanes between England and North America, it offered six-day trips across the Atlantic, from Liverpool to Quebec City via the St. Lawrence River. When the Empress was launched on her maiden voyage in 1906, she proved herself to be both dependable and swift. It was on her 96th transatlantic journey that the ship met with grave misfortune.

|

| The Empress of Ireland is shown at its launch |

At about 1:55am, the Storstad horrifyingly emerged out of the fog only 30 metres from the Empress. A collision was inevitable, despite Kendall bellowing orders for full steam ahead in an effort to move out of the way, the collier (which featured a reinforced, reverse-slanting prow ideal for breaking up the ice in its path on the Norwegian Sea) rammed the Empress at a 45-degree angle, piercing the ship between the ribs. At this point, Captain Kendall shouted through a megaphone for the Storstad to continue ahead on its engines, in hopes that the other boat would function as a plug (and delay the inevitable fortune of the stricken ship, for Kendall was likely more than aware of the fate of the ship at this point); unfortunately, the tumultuous waters of the St. Lawrence River floated the two ships apart, opening a 100 square metre hole near the bottom of the Empress. Within three minutes, the raging waters had reached the dynamos and knocked out the power, plunging the ship into darkness—but not before an S.O.S message is sent out to the port at Pointe-au-Pere, Quebec, from where two ships were dispatched in aid. Nearly all the port-holes of the ship had been left open, an occurrence that was not unusual due to the often-stifling conditions of third-class accommodation, though maritime “Safety of Life at Sea” regulations demanded that all portholes should be closed and locked before the ship leaves port. Shortly after the Empress lost power, the vessel began to take a sharp list starboard, and the river began to pour into the ship at about 225,000 litres per second. Kendall ordered the lifeboats lowered, but only nine could be launched before the ship was so much on her starboard side that lowering the rest of the boats proved to be an impossible task. By 2:05am, the ship careened violently and completely onto her starboard side, and though many of the passengers and crew died quickly (as they were sleeping in the lowest quarters), the ship resting so parallel to the water allowed for as many as 700 passengers to scramble out of her open port holes and onto her side. This stroke of luck was short-lived, however, as after two minutes the stern of the ship bobbed briefly out of the water and the hull started to sink out of sight, sliding the hundreds of people on her side into the freezing water.

By 2:10am, less than 15 minutes after the initial collision, the RMS Empress of Ireland had completely disappeared beneath the ghostly surface of the St. Lawrence River. A letter from the wife of Captain Andersen, master of the SS Storstad, will later reveal that the communal wailing got louder and louder through the blinding fog, writing, “I will never forget it, never. I still hear the screams.”

Two Canadian government steamers, the Eureka and the Lady Evelyn were dispatched to the scene, but arrived too late to save any lives. As soon as the fog had lifted, the SS Storstad found its way back to the site of collision. Captain Kendall, who had been thrown from the bridge of the ship when she lurched onto her side, was picked up by a nearby lifeboat. He immediately took command of the small boat -though he was reportedly in a near-death state- and began rescue operations, successfully pulling in many people from the icy water. The lifeboat was eventually rowed to the vessel which had pierced them, so the survivors could be dropped off. As Captain Andersen’s wife emptied her wardrobe to clothe the naked and shivering survivors, Kendall confronted Andersen for the first time, famously yelling, “You have sunk my ship!” For the next few hours, Kendall and his surviving crew made trips back and forth between the Storstad and the wreckage, until it was decided that anyone still in the water would have either succumbed to hypothermia or drowned. The newspapers at the time had difficulty reporting the death toll initially, as the numbers of those saved and lost were not accounted for until the official inquiry weeks later; there were many disparities between the identities of the passengers written in the manifest, and in the names given by the survivors. It was later established that the final death toll was 1,012; there were only 465 survivors, meaning that almost 70 percent of the persons aboard the Empress lost their lives that fateful night.

Amongst the dead was English dramatist and novelist Laurence Irving, who was alleged to have been temporarily safe until he jumped back into the water for his wife, who could not swim. His body washed ashore weeks later, identifiable only by his ring; clutched in his hand was a piece of sheer cloth, likely from his wife’s nightdress. The ship was also carrying 167 members of the Salvation Army Staff Band, who were en route to London for an international conference, but only eight survived. Only four of the 138 children aboard the Empress lived; one of these children was 7 year-old Grace Hanagan, who was, until May of 1995, the last remaining survivor of the disaster. She died the day before her 88th birthday in St. Catherine’s, Ontario.

|

| The 1st class dining saloon on the Empress of Ireland. |

|

| First Class Dining Saloon on the 'Empress of Ireland' (1906) |

|

| First Class Entrance Hall and Stairway. |

It was not long after the disaster that a salvage operation on the Empress of Ireland began. Bodies and valuables were recovered, including over one million dollars (adjusted for inflation in 2014) of silver bars. The divers did not have an easy time—though the wreck rests at a relatively shallow depth of 40 metres (compared to the Titanic at 3,784m) the divers were plagued by limited visibility and the incredibly strong currents of the St. Lawrence River. In 1964, the wreck was revisited by a team of Canadian Divers who recovered a brass bell; the bell has rested in the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Ottawa since 2012. Previous to this, the bell suffered a politically-fuelled tug-of-war between private owners and the heritage department of the Canadian government.

In 1999, the wreck site of the Empress of Ireland became protected under the Cultural Property Act, after diving scavengers were becoming more frequent. It is now listed in the Register of Historic Sites of Canada. Expert Divers can visit the wreck, given its accessible depth, but it remains dangerous. Since 2009, six people have died on this diving expedition.

There are a number of monuments to the memory of the lives that were lost with the Empress, including on the shores of the St. Lawrence River in Rimouski and Pointe-au-Pere, Quebec. The Salvation Army erected its own monument at the Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto, Ontario. A memorial service is held there annually on or around the anniversary of the tragedy.

|

| The RMS Empress of Ireland is undoubtedly one of the most fascinating, beautiful, impressive and prestigious wrecks in the world. |

|

| RMS Empress of Ireland wreck |

|

| Photograph, Damaged S.S. "Storstad", Canadian Vickers, Montreal, QC, 1914 |

|

| In memory, erected by the Canadian Pacific Raylway Compagny. For all deads of Empress of Ireland liner. Photo at Pointe-au-Père (Rimouski), Quebec, Canada. |

|

| The wreck of RMS EMPRESS OF IRELAND Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada Commemorative Plaque |

|

| Drawn postcard of the RMS EMPRESS OF IRELAND |