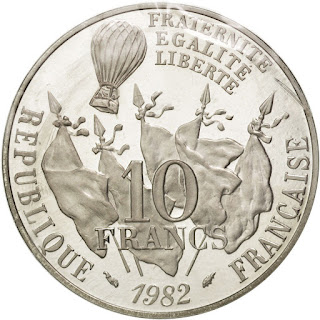

France 10 Francs Silver Coin 1982 Leon Gambetta

Commemorative issue: 100th Anniversary of the Death of Leon Gambetta

The commemorative coin of 10 francs from 1982 commemorates the 100th anniversary of death of Leon Gambetta (1838-1882) - French politician, Prime Minister of the Third Republic, which he proclaimed. Using a balloon Gambetta escaped from Paris besieged by the Germans during the Franco-Prussian War (hence the balloon motif on the coin).Obverse: below coin centre in two lines face value: 10 FRANCS; in the background five flags, above a balloon; along the top edge in three lines motto of France: FRATERNITÉ ÉGALITÉ LIBERTÉ (fraternity equality liberty); along the bottom edge: RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE (French Republic) divided by year of issue 1982.

Lettering: LIBERTE EGALITE FRATERNITE 10 FRANCS REPUBLIQUE 1982 FRANÇAISE.

Engraver: Émilie Rousseau.

Reverse: Bust of Leon Gambetta facing left; along the left edge in two lines: LÉON GAMBETTA 1838-1882.

Lettering: LÉON GAMBETTA 1838-1882 ER.

Engraver: Émilie Rousseau.

Face value: 10 Francs.

Edge: plain.

Designer: Émile Rousseau (initials ER behind Gambetta's neck in the reverse).

Mint: Paris Mint mark La Monnaie de Paris (The Paris Mint), Pessac (mint mark before year of issue 1982 in the obverse, after year of issue privy mark of designer and mint's director Émile Rousseau - dolphin).

Mintage: 3 044 511 + 27 500 in annual boxed sets.

Composition: Nickel-Bronze.

Weight: 10 g.

Diameter: 26 mm.

Thickness: 2.6 mm.

Léon Gambetta

Léon Gambetta (born April 2, 1838, Cahors, France — died Dec. 31, 1882, Ville-d’Avray, near Paris), French republican statesman who helped direct the defense of France during the Franco-German War of 1870–1871. In helping to found the Third Republic, he made three essential contributions: first, by his speeches and articles, he converted many Frenchmen to the ideals of moderate democratic republicanism. Second, by his political influence and personal social contacts, he gathered support for an elective democratic political party, the Republican Union. Finally, by backing Adolphe Thiers, who was elected provisional head of government by the National Assembly of 1871, against royalists and Bonapartists, he helped transform the new regime into a parliamentary republic. Gambetta was briefly premier of France from Nov. 14, 1881, to Jan. 16, 1882.

Gambetta’s mother was from Gascony; his father was an Italian who had emigrated to Cahors and had opened a grocery store there. A successful pupil at the local high school, ambitious and naturally eloquent, young Gambetta refused to stay in a provincial town with no other prospect than to work in his father’s store. Against his father’s will, he went to Paris to study law.

Gambetta professed very strongly republican opinions, and his exuberant and generous nature soon made him highly popular among the Paris students. In 1859 he was called to the bar, but he was unsuccessful as a lawyer until 1868, when a political case known as the Affaire Baudin made him suddenly famous. Jean-Baptiste Baudin, a deputy (legislator) killed resisting Napoleon III’s coup d’état of 1851, had become a republican martyr, and eight journalists were being prosecuted for attempting to have a monument erected in his memory. As counsel of one of the accused, Gambetta delivered an extremely forceful speech in which he indicted the imperial regime, its origin, and its policy.

Press reports of his speech made his political fortune, and almost overnight Gambetta became an acknowledged leader of the Republican Party. In 1869 he was elected to the Legislative Assembly. He opposed the steps that led to the outbreak of the Franco-German War in July 1870, but, once it had begun, he urged the quickest possible victory over the Germans. After the disastrous defeat of the French at Sedan, in which Napoleon III was captured on Sept. 1, 1870, Gambetta played a principal role in proclaiming the republic and forming a provisional government of national defense. He became minister of the interior in this government.

The most pressing problem of the provisional government was the defense of Paris, which was besieged by the Germans. Most members of the government stayed in the city, but Gambetta, as their delegate, left Paris in a balloon on Oct. 7, 1870, floating over the German lines. Establishing himself at Tours, he began to arouse unoccupied France for the defense of the entire country. He became war minister as well, assuming virtually unlimited powers.

Of the two main French armies, one had been captured at Sedan, and the other was besieged at Metz and soon forced to surrender. Gambetta, as always enthusiastic and indefatigable, succeeded in raising new armies, which were trained and supplied with arms. These achieved some local successes but were more often defeated.

When Tours was threatened by the Germans, Gambetta left for Bordeaux in southwestern France. Though he wished to continue fighting, the country was tired of war, and the provisional government signed an armistice on Jan. 18, 1871.

The armistice convention provided for the election of a National Assembly, which met at Bordeaux in March 1871 to ratify the peace terms. Gambetta was elected a deputy for Strasbourg, in Alsace, but, after the ratification of the peace, which yielded most of Alsace and Lorraine to Germany, he lost his seat and retired for a short time to Spain.

In by-elections in July 1871, he was elected to the National Assembly by the département of the Seine. The assembly was to determine whether France would remain a republic or restore the monarchy. The majority of the deputies were monarchists. There were, however, two candidates to the throne, the heads, respectively, of the elder and the younger branch of the Bourbons, and they were unable to reach agreement on which should become king. With supreme skill, Gambetta managed to push ratification of the republic through the weary assembly. The republican constitution of 1875 formed the basis of the French Third Republic until the latter’s demise in 1940.

Parliamentary intrigue prevented Gambetta from being elected president of the republic, but he became president of the Chamber of Deputies, a position in which he exercised great power. He attempted to promote a tolerant republic, an “Athenian republic,” as he described it. In spite of his corpulence, disheveled beard, and badly groomed appearance, his natural warmth, generosity, and liberalism made him highly popular.

Jules Grévy, the president, disliked Gambetta and for a long time refused to ask him to form a government. After Gambetta at last was appointed premier in November 1881, he pursued, in foreign affairs, a policy of establishing a closer relationship with Great Britain and, in domestic affairs, an ambitious program of domestic reform. He was overthrown in January 1882 before achieving either goal.

In 1872 he began a liaison with Léonie Léon, a pretty, well-educated woman, and, after his resignation, he settled with her outside Paris, with the intention of marrying her. While handling a revolver, he shot himself in the arm, and, as his health was very poor, the wound healed slowly. During his convalescence, he was stricken with appendicitis, but the doctors did not operate. He died on Dec. 31, 1882, at the age of 44.

Gambetta was honoured with a national funeral. His reputation has remained largely undiminished; there is hardly a town in France without a street bearing his name. Yet his fame rests on what he achieved in his long years of opposition and during the Franco-German War rather than during the two terms — totaling three years — in which he exercised power. He was a fervent advocate both of fully modern democracy — universal suffrage, freedom of the press, right of meeting, trial by jury for political offenses, separation of church and state — and of national unity. For the sake of the latter, he occasionally struck bargains with his political opponents, thus gaining an undeserved reputation as an opportunist. Undoubtedly, he was largely responsible for the consolidation of parliamentary democracy in France, but his compromises resulted in a fragile party system that served to weaken democratic government.